The Working of Hearing and Balance in the Ear

Our ear is divided into three parts: the outer ear, middle ear, and inner ear. The outer and middle ear are primarily responsible for hearing, while the inner ear contains special structures that help with both hearing and balance. In this article, we will mainly focus on the fascinating workings of the inner ear.

The inner ear, also known as the labyrinth (which is why the condition labyrinthitis refers to inflammation caused by infection), can be thought of as a house with two specialized rooms, both connected by the same hallway and plumbing.

One room is the Sound Room, where hearing takes place. This is also called the cochlea. The other room is the Gym with Balance Equipment, where balance is controlled. This is known as the vestibular system.

Though separate, these two systems sit side by side. They share the same nerve and blood supply, but they perform different functions. Let’s walk through each room.

The Sound Room: How We Hear

Sound starts outside the ear. When it enters, it travels down the ear canal and strikes the eardrum, causing it to vibrate—like a drum skin being tapped. Attached to the eardrum are three tiny bones, the smallest in the human body:

- Hammer

- Anvil

- Stirrup

These bones act as a mechanical amplifier, passing and boosting the vibrations into the cochlea, the main hearing organ.

The Cochlea: Where the Magic Happens

The cochlea is shaped like a tiny snail shell, filled with fluid and lined with thousands of microscopic hair cells.

When vibrations enter the cochlea:

- The fluid moves.

- The hair cells bend.

- This bending converts mechanical sound vibrations into electrical signals.

These electrical signals are then sent along the hearing nerve to the brain, where they are interpreted as:

- Speech

- Music

- Noise

At this point, sound is no longer sound—it’s electricity. The brain correlates these electrical patterns with memory and language to interpret their meaning. The hearing part is also connected to the emotional system in the brain. This is why certain sounds are soothing (like music), while others are perceived as threatening (like a fire alarm).

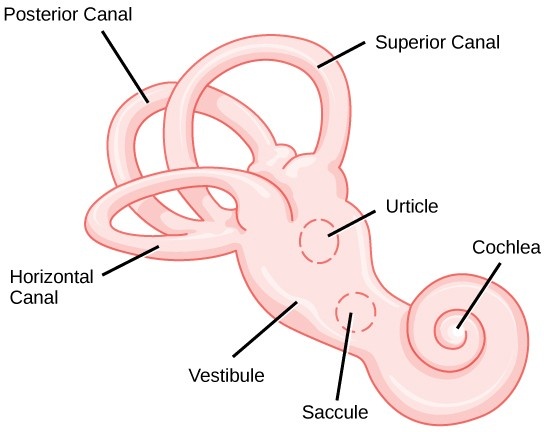

The Vestibular System: How Balance Works

Now, let’s step into the balance room. This room contains two main parts:

- Three semicircular canals that sense the angular acceleration of the head.

- Two otolith organs that sense the linear acceleration of the head.

The Semicircular Canals: Your Internal Gyroscope

Inside each inner ear are three semicircular canals, positioned at right angles to each other—just like a 3D gyroscope. Every time you move your head at an angle:

- Turn

- Nod

- Tilt

The fluid inside these canals moves and bends hair cells. This motion is converted into electrical signals and sent to the brain via the vestibular nerve.

The brain instantly knows:

- Your head is moving.

- Which direction.

- How fast.

The Reflex That Keeps the World Still

Once the brain receives the signal about head movement, it automatically activates your eye muscles so that your eyes move equally and oppositely to your head.

You don’t think about this. You don’t control it. It just happens.

This automatic response is called the Vestibulo-Ocular Reflex (VOR). It’s the reason you can:

- Read a sign while walking.

- Keep your vision stable while turning your head.

- Avoid seeing the world shake like a blurry video.

Without this reflex, balance would quickly fall apart.

Sensing Motion Without Turning

There are situations where your head doesn’t move at an angle but is carried along with your body—like when you’re in a car or a lift (linear acceleration). This is where the otolith organs come into play. These organs tell the brain where your head and body are in space, even when your head isn’t turning.

The otolith system consists of two parts:

- Saccule – Horizontal Movement

- Detects forward, backward, and side-to-side motion.

- Example: Sitting in a moving car.

- Utricle – Vertical Movement & Gravity (Determining “Down”)

- Detects up-and-down movement.

- Example: Being in an elevator.

- The utricle also helps us sense gravity by using tiny calcium crystals on its surface, much like sand on a drum skin.

When the Crystals Go Rogue: BPPV

Sometimes, the calcium crystals in the utricle become dislodged. When this happens, they can fall into one of the semicircular canals, where they shouldn’t be. This causes the brain to receive false signals when you move your head, leading to:

- Sudden spinning sensations.

- Dizziness when turning in bed.

- Vertigo when looking up.

This condition is called BPPV (Benign Paroxysmal Positional Vertigo):

- Benign – not dangerous.

- Paroxysmal – sudden.

- Positional – triggered by movement.

- Vertigo – spinning sensation.

Annoying? Yes.

Common? Definitely.

Treatable? Thankfully, yes. A trained audiologist, vestibular physiotherapist, or ENT surgeon can treat BPPV with a simple, harmless maneuver in a clinic, often leading to 100% improvement in minutes.

Same House, Different Rooms, Different Problems

While hearing and balance both live in the same inner ear and share nerves and blood supply, they are separate systems. This explains why you can:

- Have dizziness with normal hearing.

- Experience hearing loss with perfect balance.

- Or have problems with both, depending on where the issue begins.

When Things Go Wrong: How We Test Hearing and Balance

When something goes wrong in the cochlea (the sound room), people experience hearing problems. To assess this, a hearing profile is used to measure how well different sounds are detected and understood. This includes pure tones that make up speech and music, as well as real speech sounds, tested in both quiet and noisy environments. A comprehensive evaluation also includes objective hearing tests that assess the movement of the eardrum, the transmission of sound through the middle ear, and the response of the cochlea to sound.

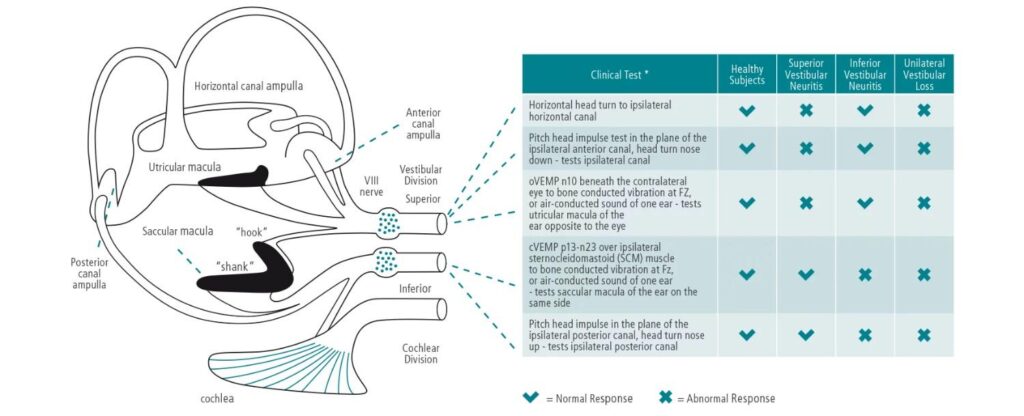

When something goes wrong in the balance room, dizziness, vertigo, and imbalance can occur. To evaluate this, we test the function of the semicircular canals using specialized assessments like the Video Head Impulse Test (vHIT) and caloric testing, along with other tests in a comprehensive balance test battery. We also assess the otolith organs using Vestibular Evoked Myogenic Potentials (VEMPs), and examine how well the brain coordinates balance information with eye movements in changing visual environments using Video Nystagmography (VNG).

Our hearing and balance are vital senses, helping us connect with and navigate the world. The intricate mechanisms behind these functions are nothing short of remarkable. A thorough understanding of this sophisticated system, combined with state-of-the-art equipment, enables accurate diagnosis and treatment in a good audiology clinic.

Pic: How various different balance tests help to create a picture of fault in the balance system in the ear